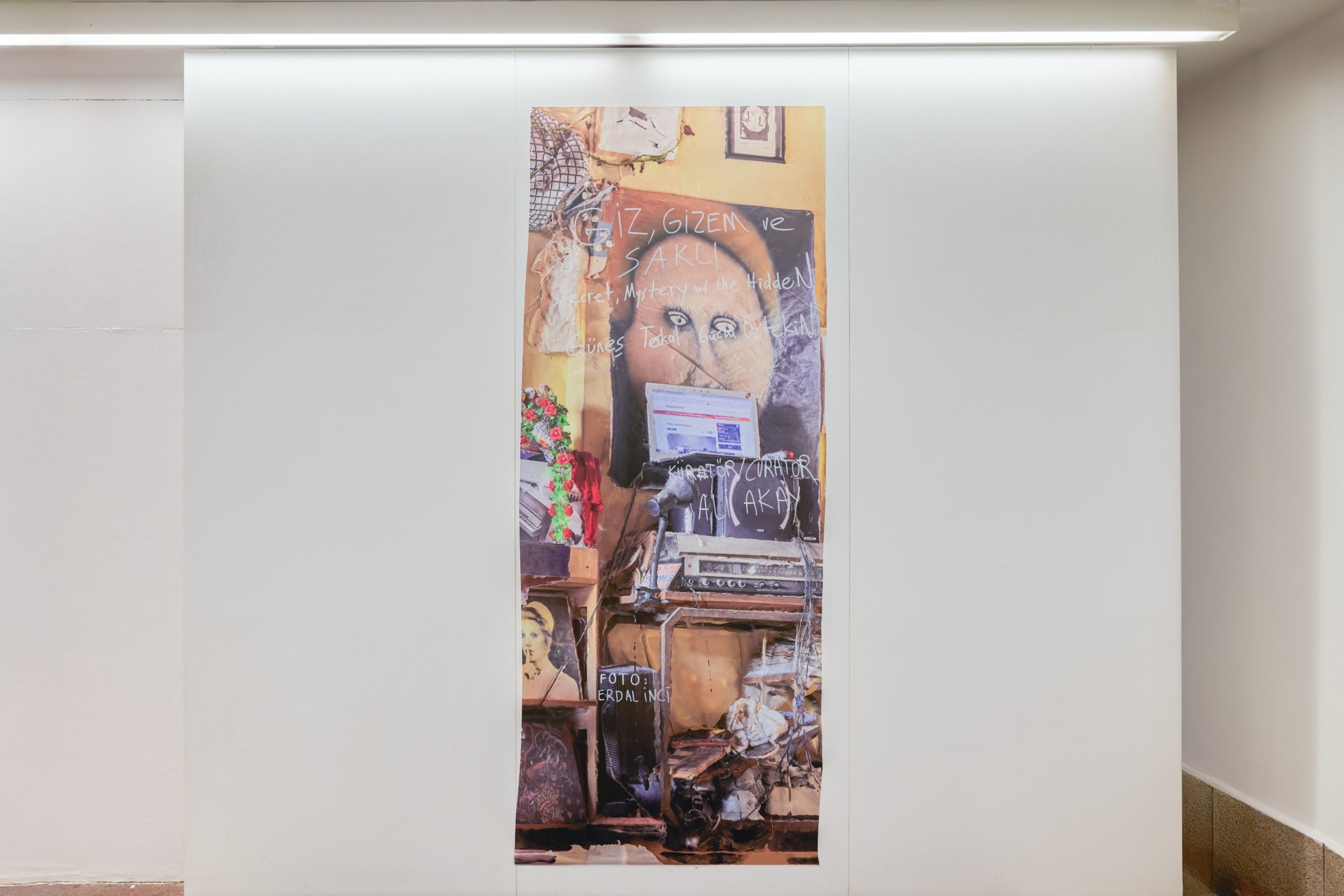

GÜNEŞ TERKOL & GÜÇLÜ ÖZTEKİN

Curator: Ali Akay

“Word, word, here in the right place of the pains, word, Gentlemen.

This is the most important task belonging to the public.”

Hugo Ball, 1916

The world in which we are living is a world that restricts the “joy of living.” How can we look at this? By hiding our joy? Or by laughing inwardly? We laugh because we need joy. Our curiosity — our sincere curiosity toward the things that seem hidden — is also for this reason. We want to learn what is concealed from us: the writings, the ideas, the thoughts, and especially history and geography. Not the kind taught in school; rather, it is an effort that requires research.

This exhibition, in my opinion, works to cast out — to externalize — our worlds that appear entirely pitch-black and full of unhappiness today, along with our inner distress. The disclosure of an intimate secret is not meant as a confession or a pouring out of one’s heart, but to present a joyful spectacle. Artists are needed in times of wars, injustices committed in unjust places, and in the moments when the blade of justice goes astray. Their existence brings both joy and thought. Sometimes they bear the burden of history; sometimes they pull it elsewhere. But is not the essential point to expel and reveal the hidden and inner joy? This exhibition proposes one of the beginnings of an outward expansion movement — to learn the secret of the things we live within, as much as it is dedicated to secrecy and mystery. In that regard, it attempts to stand within “joyful days.” Just like in the film, when others arrive and begin to cast aside past beauties, joy itself must be what resists — and we imagine that it will. Then we forget the crowds, and a feeling circulates around us as if we could pass through the world that has ended and recreate it again.

In his text “Fusées”, C. Baudelaire speaks of “the end of the world.” The ended world is not only the loneliness of individuals within society, as in his other writings; but here, is he not speaking of the end of politics? It is also not the intermingling of crowds within a democratic environment. In other words, it is not the public space that is the place of politics. The crowd is everything but it is NOT A DEMOCRATIC SPACE. Nor is it the people gathered under the charisma of a dictator. It is not the crowd that came to listen to Mussolini or Hitler in Italy or Germany at the beginning of the last century. This crowd, described as the crowd of the modern city, has grown far from politics and far from being the site of public space. In this sense, while J. Derrida interprets this text, he uses the concept of the apocalyptic in relation to the political; because each person hides themselves within this crowd. Each hides as someone among others in the modern cities of the 19th century. The Chinese — I believe — were the first to find a solution: they invented electronic control devices that individually target each person.

Baudelaire, after saying that “the world has ended,” immediately continues: it has ended, but the world still exists; because he connects what exists and what does not with a sentence like “it is present,” “it exists.” This is a sentence like in the Sura of the Apocalypse: “Apocalyptic lack of politics.” Among the crowds, people hide themselves. Just as in demonstrations everyone wants to become visible, in crowds each individual hides to the same extent. What ends the world is “universal evil” and “universal progress” and “universal collapse,” all standing side by side. Here Baudelaire writes that he speaks “like a prophet.” He therefore presents a prophecy belonging to the Apocalypse. He complains of crowds and speaks of the difficulty of even finding a doctor within such crowds. And thus, whatever remains of politics — these crowds will do nothing but use it violently like animals.

Baudelaire’s texts “The Crowd” and “Fusées” appear to be kin to each other. Those hiding among the crowds are like money, documents, gold secretly kept inside a vault. Much like those who hide themselves within crowds. Here plurality and loneliness stand side by side. Does the happiness and secrecy of crowds bring joy? Baudelaire underlines that there is no difference between multitude and solitude. Either way. Alone or hidden among the crowd.

The poet thought the same for the artist. The modern artist is both a person of the world and a person of the crowds; and also a child. Here hiding comes to the forefront: in Latin “cernere” (to separate, to separate by hiding) and in Greek “krupsis” (the act of hiding itself). To hide, to hide oneself, to keep something concealed. Even to disappear by hiding. To pretend to be nonexistent. To begin a game like hide-and-seek. Here other words also come: the hidden, stamped (buffered), secrecy, a person entering a country secretly, the hidden one, the illegal worker. The one who hides hides from the State and the informers within society. Those hidden, like those stored in a safe, do not wish to come to light; they come out at night. They live in a criminal mode of hiding. The Secret Police therefore gains function here: the police responsible for capturing crime (the closeness between politics and the city — polis). Those who make themselves invisible in the crowds.

Today, when we see a crime committed in crowds (social media shows this frequently), journalists not only ask where the hidden one is hiding but perhaps also make guesses. Within secrecy, of course, there is crime and police. The word police comes from the same place as politics. In the relation between the police and the city, it is the secret police; infiltrating the crowds to carry out provocations in a demonstration or a funeral ceremony, or as once happened — opening fire in Taksim Square on May 1, 1977. The work of the secret service is to make something hidden and invisible become visible through an event.

The one hidden within crowds and carrying out an attack — a person coming from the realm of the art of murder. Someone who had killed their own children years earlier. Does it matter whether murder is committed in a private or a public space? One is secret; the other is a sudden phenomenal self-emergence of someone hidden. Their name starting to be published in the media. Foucault, in an article he wrote in 1977, speaks of this: of the existence of “vile people.” That is, through committing a crime, someone who had no visibility by the power suddenly becomes visible — passing through these relations. Today, someone hidden among the crowd makes themselves phenomenally visible by committing a crime.

Does that which is secret, hidden, accepted as a mystery, begin to be revealed — to become transparent — with the era of disinformation, with false news and the spread of populism’s power through social media? Or will the distinction between the unreal and the real be brought to the outside from the inside? What remains hidden and is accepted as intimate today, is revealed to the public — as a demonstration of fidelity to the truth.

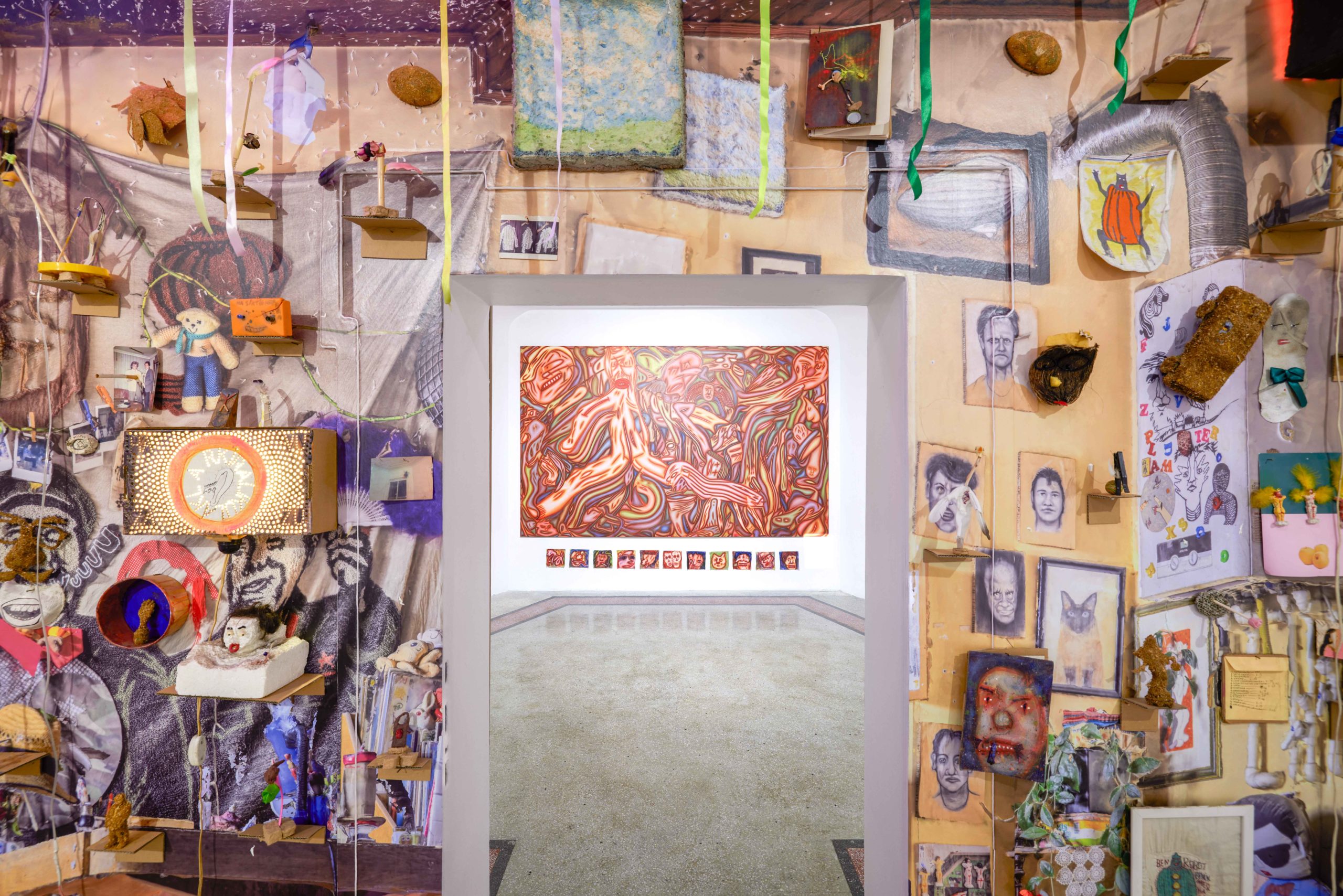

The relocation of a part of the private realms of artists Güçlü Öztekin and Güneş Terkol — of their homes and studios — into the gallery space is the revelation of hidden and intimate privacy. Each piece has different dimensions. Some are larger, some are smaller. As they grow, their visibility increases; as they shrink, their visibility decreases. Smallness and shrinking relate to secrecy. If a work is less visible and its visibility diminishes among others, then its normality also decreases. This is something Georges Canguilhem wrote in his book The Knowledge of Life (1965). After writing that human normality has dimensions and proportions, he explains that if a figure grows and becomes monstrous, they step out of human norms and become a-norm. And the French word “énorme” means “beyond the norm,” that is, “very large.” A great mountain is “énorme,” meaning it is enormous. Shrinking and becoming minuscule bring another word along. When something becomes small enough to become invisible, it becomes “hidden.” It hides itself.

This exhibition by Güneş Terkol and Güçlü Öztekin transports elements of home and studio into the gallery space, and because some works are very large and some very small — according to their scale — they become excessively visible or excessively invisible and therefore remain concealed and hidden among the others. The numerous details of the installation objects, at first glance, present a heterogeneous assemblage. Separate small (minor) sculptures, lamps, bulbs, various types of constructions, miniature structures composed of composite objects, composite sculptures, toys etc. These evoke the visual Dada movement like an indigenous world. At times we cannot help thinking of Raoul Hausmann, sometimes Francis Picabia (Portrait of Cezanne, Renoir and Rembrandt), Franz Wilhelm (The Working Men), Kurt Schwitters, or sometimes Pino Pascali or Gérard Deschamps from the 1960s. Güçlü Öztekin’s perspective on the art history of the 1920s and 1960s enables us to look at existing works again today. What is intriguing in Güneş Terkol’s works is the concealed information carried by hidden letters. As this information is decoded and what is hidden is revealed, the preservation of secrecy in these letters produces a distressing feeling. The letters sewn onto tulle are present openly but do not disclose information. Each conceals anxiety yet reveals none. They evoke curiosity, yet remain secret and hidden. This exhibition presents the secret and the self-evident side by side, without contradiction — and leads us to think together about dozens of intimate objects that provoke curiosity.

Güneş Terkol & Güçlü Öztekin are founding members of the HaZaVuZu and GUGUOU collective in Istanbul, who work across music, video, performance and design. Terkol is an artist who produces sewn works, videos, sketches and musical compositions in order to – often humorously – consider gender relations. Öztekin makes large-scale drawings and paintings on paper, that he describes as a form of ‘recycling’. For the exhibition Terkol and Öztekin built a space that is a meeting point for visitors in the show. The space contains paintings, tulles, curtains, sculptures, masks and costumes. The result is a convivial place for viewers to mingle, while reflecting the production of two artists and their shared or divergent visions.

Güçlü Öztekin (1978, Eskişehir) lives and works in Istanbul. Öztekin is known for his large-scale works created with materials such as styrofoam and craft paper. He uses materials that are within his reach as an act of recycling. Öztekin is a member of Ha Za Vu Zu, an artist collective founded in 2005 and also plays for the avangarde music group GuGuOu. His most recent solo exhibitions are Topsy-Turvy! Selpakla Gorili Bitirdim, Dirimart, İstanbul (2017); Şe Şe Pa Pa... Sometimes You Need to Cry to Fish, Rampa, Istanbul (2015); Everything’s Tickling Each Other, Krinzinger Projekte, Vienna (2012). Together with Ha Za Vu Zu, he took part in various group exhibitions, during which he enacted performances and showed his works, including 10th Lyon Biennial (2009); Bovisa Triennial, Milan (2008); 10th Istanbul Biennial (2007).

Güneş Terkol (1981, Ankara) lives and works in Istanbul. Terkol takes inspiration from her immediate surroundings, collects materials and stories which she weaves into her sewing pieces, videos, sketches, and musical compositions. She is also a member of Ha Za Vu Zu artist collective and GuGuOu music group. Recent solo exhibitions include She wasn’t there and she couldn’t believe her ears, Galeri Nev Ankara (2019), Home is my Heart, Krank Art Gallery, Istanbul (2017), The Holographic Record, NON Gallery, Istanbul (2014), Dreams on the River, Organhause, Chongqing, China (2011). She was featured in; 16th Sharjah Biennial (2025), 6th Mardin Biennial (2024), 60th La Biennale di Venezia (2024), 17th Biennale Jogja (2023), 17th İstanbul Biennial (2022), 16th İstanbul Biennial (2019), Passion, Joy, Fury, MAXXI, Roma (2016); 10th Gwangju Biennale, South Korea (2014); Better Homes, Sculpture Center, New York (2013)., 2nd Antakya Biennial (2010) and has participated in residencies; Art Explora (2022), Borderline Offensive Artists Residencies (2018), Cite Internationale des Arts (2016), ISCP New York (2013), Organhaus Chongqing (2011), Gasworks (2010).