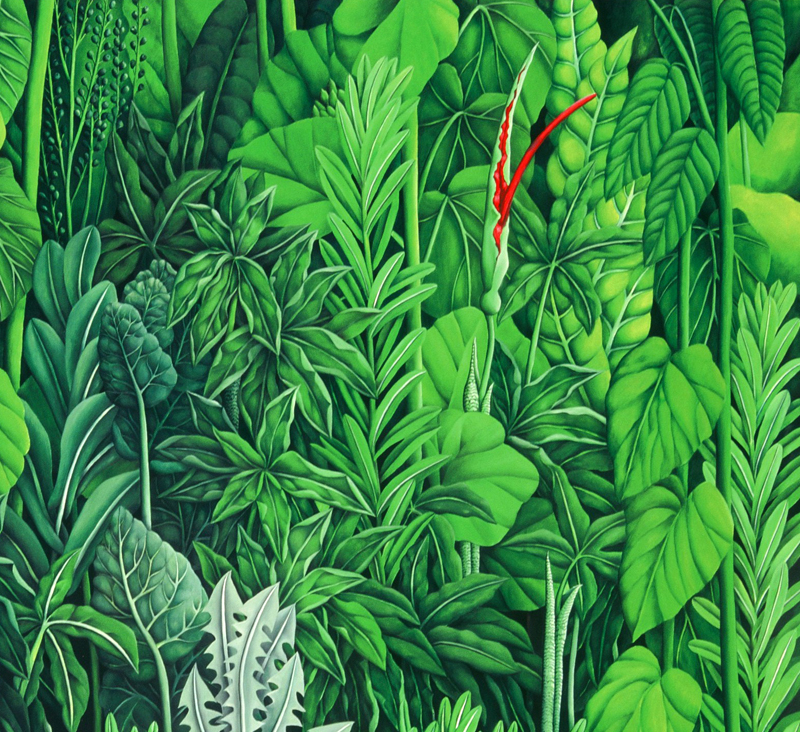

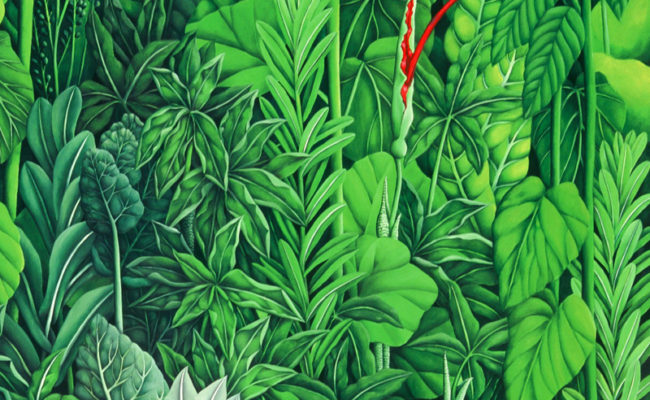

Nadide Akdeniz has continued her artistic career in an uninterrupted manner since the early 1970s, and perhaps the most appropriate definition of her is “the green sorcerer of the great green world”[1]. Nadide Akdeniz constructs fairy-tale-like green landscapes that cross and intersect social, cultural, ecological, political and spiritual worlds. Her paintings display a refined sensibility, and provide an alternative to the popular tendencies of her period. The organic universe of the artist that begins to live and move with plants, trees, leaves, ivy, fruit and flowers completely fills the surface of the canvas, forming the flora that becomes the style, now synonymous with the artist. Her dreamlike landscapes become, in a sense, her magical, green pseudonym. In Nadide Akdeniz’s fantastic-realistic world, objects that appear as indicators of an ordinary life become symbols indicating society/humanity/time. The fictive, psychological and socio-cultural suggestions of a white cloth, a teapot, a kettle, a hat, a chair, a shoe, a mannequin or an oxygen cylinder take their place in her paintings as loaded metaphors. The cultural baggage of identity, life’s feminine cycle, womanhood, eroticism and sexuality reveal themselves within a feminine symbolism that displays no timidity. Akdeniz, in her works produced after the 1990s, interblends objects, forms and situations. The artist’s paintings reflect, in a grotesque and ironic style, all motifs and images that seem impossible to bring together, presenting the viewer with an emancipating experience of infinite expression between humanity and nature, society and culture and dream and reality.

Armchairs, tables, wardrobes, drawers, curtains and mirrors that we encounter in Nadide Akdeniz’s charcoal-on-paper “untitled” works are concealed feminine reflections that contain the meaning of “home”. In addition to the dialectics of the interior and exterior of houses, with her domestic furniture that we observe as placed both in interiors and exteriors, the artist sensitively investigates all the positive and negative allusions of womanhood, family, belonging, attachment, origins, forgetting and remembering via tangible objects. In the “untitled” work of the artist dated 2019, in one of the two planned scenes, there is a figure who issues directives with a camera behind, and a loudhailer in hand. This figure, that appears to be a director, speaks to the crowd of people in the opposite scene. There is a skyline between the director and these people who walk in procession with their backs to us, as if they are heading to the unknown. The sea and the sky, partially visible in the horizon, alleviate the uncertain disquiet we sense when we wait for the happy ending of a film. In her “untitled” charcoal on paper works from 2019, too, just like the camera crew hiding behind vegetation, or the land surveying device surrounded by men in suits, elements such as cameras, base station poles, helicopters, observation towers, lifeguard towers and ‘no entry’ tape operate as signs of the oppressive, controlling and prohibitive society of discipline that has emerged in the Mediterranean flora.

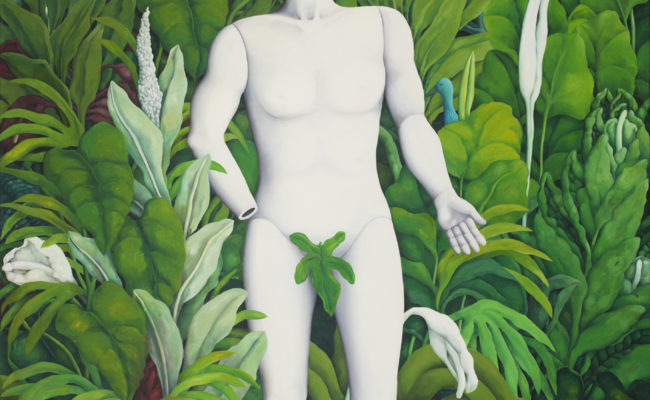

The apple features in the story of Adam and Eve, too, and frequently in holy texts, mythology, folk stories and fairy tales, as a symbol that triggers a series of events that often end in disaster. Perhaps for this reason, and despite the apple appearing in many of her paintings, Nadide Akdeniz’s “Adam and Eve” from 2000, points not to the presence but absence of the apple, and operates both as a mythical and fantastic, and as a socio-critical work. Two lifeless mannequins stand motionless in the middle of a false paradise, and the snake can barely be discerned from among the leaves. Although we cannot clearly see the snake, its “dangerous” presence is felt. Yet there is neither an apple to be seen to cause a disaster, nor Eve, to invite Adam to sin. Eve has no sex organ, in a criticism against the historical position of “woman” as a spectacle. In contrast, Adam’s sex organ is hidden behind a leaf, reflecting in an ironic and playful manner, yet also with sharp criticism of gender roles, the concealed phallus as the symbol of “power”. The reputed status of phallus is fake, counterfeit.

Derya Yücel

Curator

NADİDE AKDENİZ: In 1966, she graduated from Gazi Education Institute, Department of Painting and Graphics. She was the student of Turan Erol, Adnan Turani and Nevide Gökaydın. She received his bachelor's degree from Dokuz Eylül University Buca Education Faculty Art Education Department. Shee worked as a graphic artist for a while. She worked as a teacher and graphic designer in secondary education and higher education institutions, in Izmir Buca Education Institute between 1975 and 1980, and in Ankara Gazi Education Institute in 1975 in accelerated education programs. In her early paintings, an understanding that includes ironical elements in places, within the framework of a critical observation of urban life and people, predominated; From the 1990s on, she turned to a new narrative in which he interpreted the details of nature with a photorealistic technique. These paintings draw attention with meticulous workmanship and a colorist attitude dominated by blue and green tones. The artist living and working in Istanbul.

[1] Marianne Pitzen “Büyük Yeşil Dünyanın Yeşil Büyücüsü: Nadide Akdeniz [The Green Sorcerer of the Great Green World: Nadide Akdeniz], Treffen Im Dscungel/Cangılda Buluşma Exhibition Catalogue, Frauen Museum/Bonn, March 2001